The 1862 Exhibition – The Rarer Views

The

1862 Exhibition was intended as a sequel to the Great Exhibition of 1851,

to showcase Britain's emerging might, but also to encourage free trade

between nations – the lion's share of which the British Government rightly

predicted would come their way. The Exhibition was to be held in a purpose-built

building on London's Brompton Road (where the Natural History Museum now

stands), and there was never any hope of housing it in such an iconic building

as Paxton's Crystal Palace. Despite fierce competition among architects,

the design of the winner, Captain Francis Fowke, was not well received,

and the leading architectural magazine of the day declared that 'its ugliness

is unmitigated'. Dubbed the 'Brompton Boilers' due to its twin domes, it

was promptly demolished afterwards as, apart from its unpleasing appearance,

the roof leaked, the drains didn't work properly, the use of large amounts

of cast iron caused the building to heat up uncomfortably, and the upper

floors were too weak to hold all the exhibits safely.

Other

factors threatened to derail the Exhibition. Prince Albert had been involved

in the planning (as he was with the Great Exhibition) and with Queen Victoria

was expected to attend the opening ceremony. Unfortunately he thoughtlessly

died in December 1861 plunging the Royal Family and most of the British

aristocracy into deep mourning – the last thing on their minds was an Exhibition.

The

USA was expected to send a large display but the Civil War put paid to

that – although some exhibits were sent over.

Against

all the odds, however, the Exhibition was a roaring success. Between 1

May and 15 November 1862 6.2 million paying visitors went thru the turnstiles.

Photography had come a long way in the decade of the 1850s and was now a big money spinner. The London Stereoscopic Company under George Nottage secured the exclusive photographic rights for the massive sum of £3,000 (then $12,000). William England working under contract was the main photographer but other big names such as Stephen Thompson and William Russell Sedgfield were pressed into service. Photography was restricted to certain hours in the early morning and evening so crowds do not appear. One of the complaints from visitors was that large clouds of dust were churned up by the many feet, so early morning was probably when most views were taken. Some people do appear, often the same ones in several views.

Several

hundred thousand views were produced and they can be found, although often

in poor condition. It seems, however, that Victorian tastes were much different

to ours. The most popular – and therefore the most common – were the statuary

views, especially classical statues of young ladies déshabillé.

They probably make up 80% of what is available. The rarest are the

views which we probably find the most interesting – views of machinery

and workmen operating them. As in general photography of the period, the

working classes and their activities were not considered to be subjects

of interest.

The

series of views run to some 350 in all and, in general, the higher the

number the harder the view is to find.

Fig.

1. Shows the Dining Rooms, an inspired choice for us 150 years later but

not a good seller judging by the number of this view that survive. A temporary

exhibition venue was built along Cromwell Road. The dining room overlooked

the gardens of the Horticultural Society.

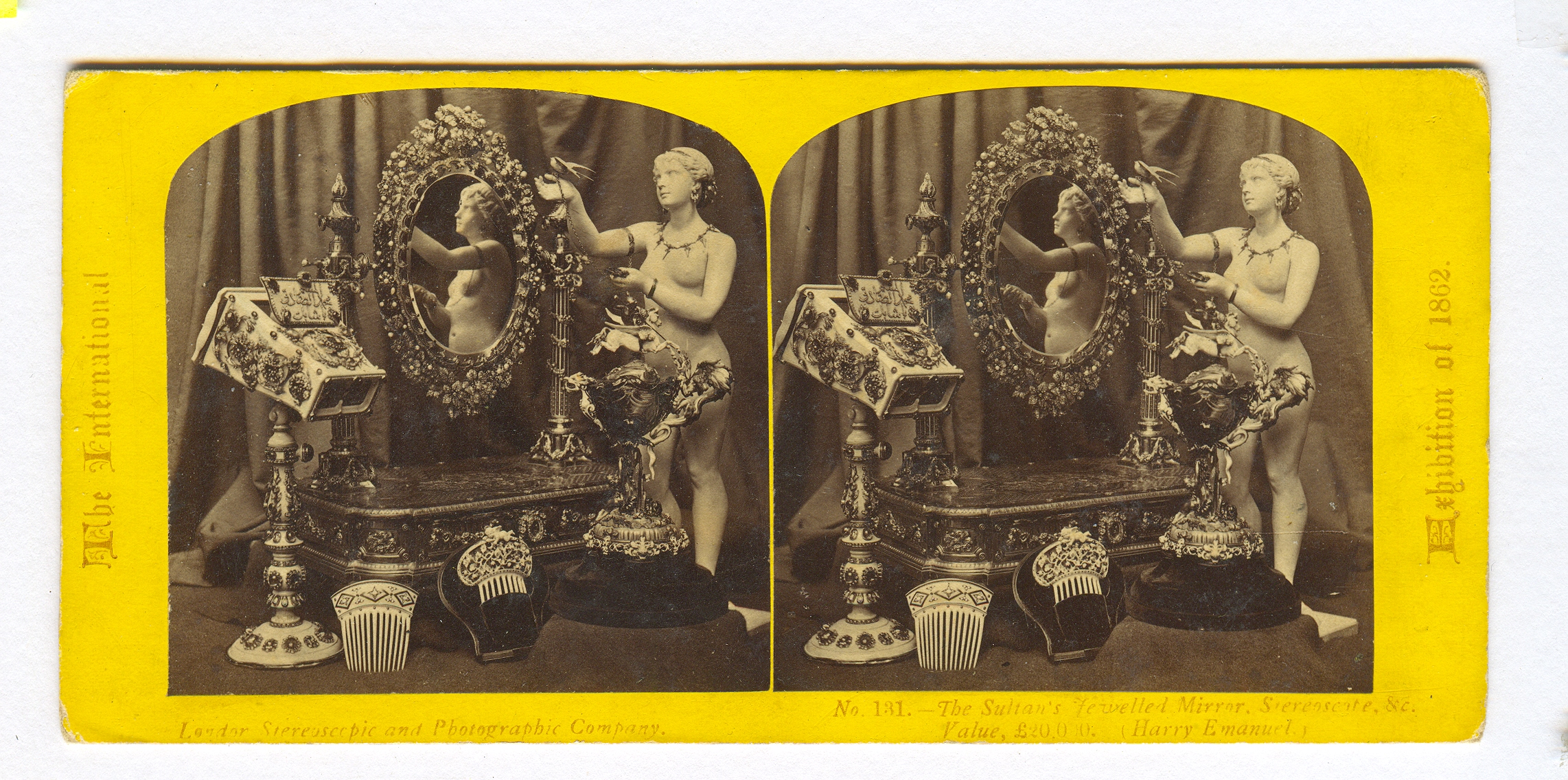

Fig.

2. The Sultan's Jewelled Mirror, Stereoscope, &c. Value £20,000.

(Harry Emanuel). A list on the back states that the objects are from Harry

Emanuel, Queen's Jeweller, 70 & 71 Brook Street, and Hanover Square.

Emanuel took over his father's jewellery business in 1855, and in 1865

followed his work in ivory with the use of feathers and plumage in jewellery.

His patented technique involved the glueing of feathers to prepared mounts

using shellac. He retired in 1873, and later became, at his own expense,

the Minister Plenipotentiary (Ambassador) of the Dominican Republic in

France. He died in Nice in 1898.

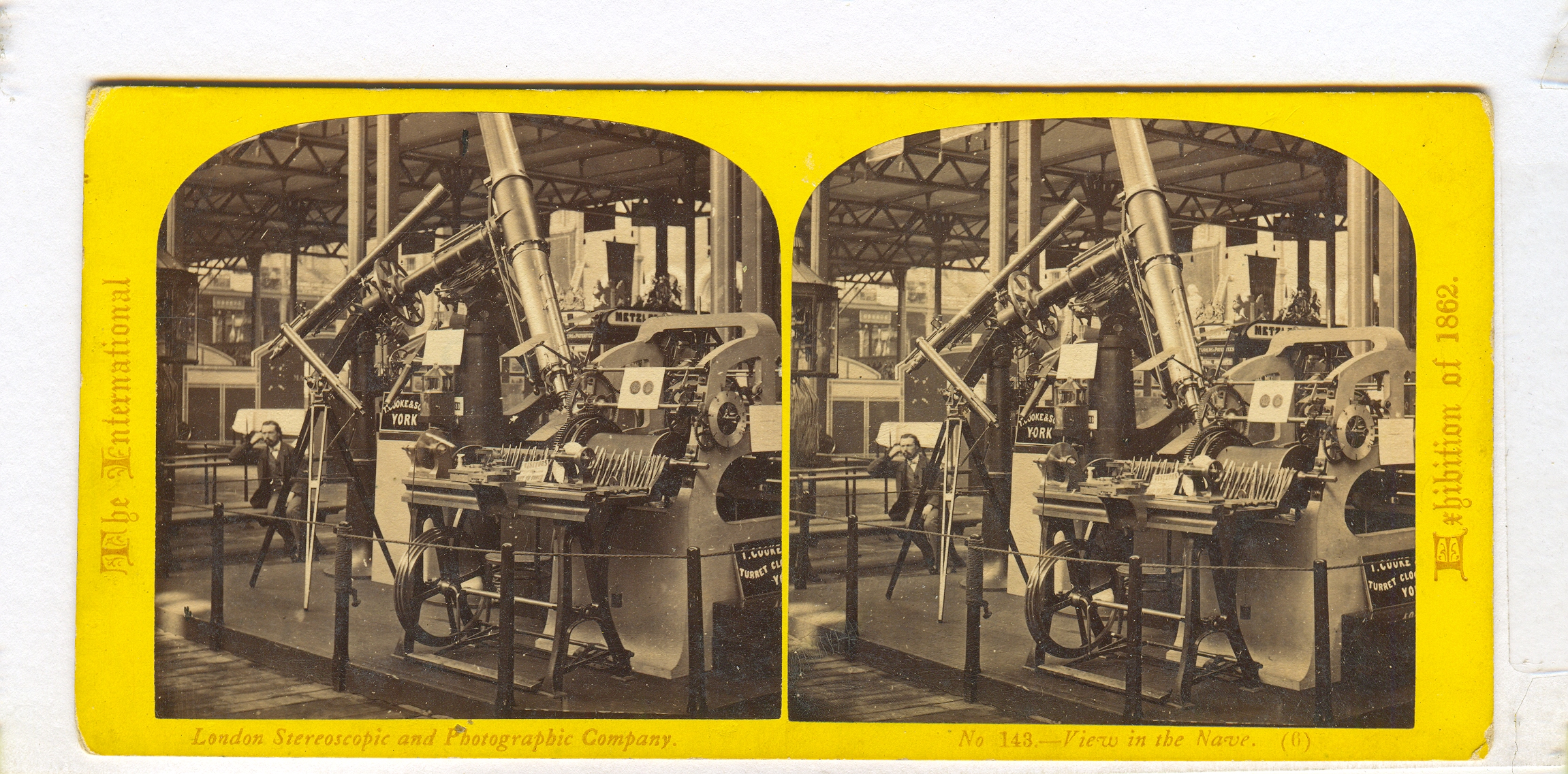

Fig

3. View in the Nave (6). Showing a turret clock in the foreground and what

looks like a telescope beyond.

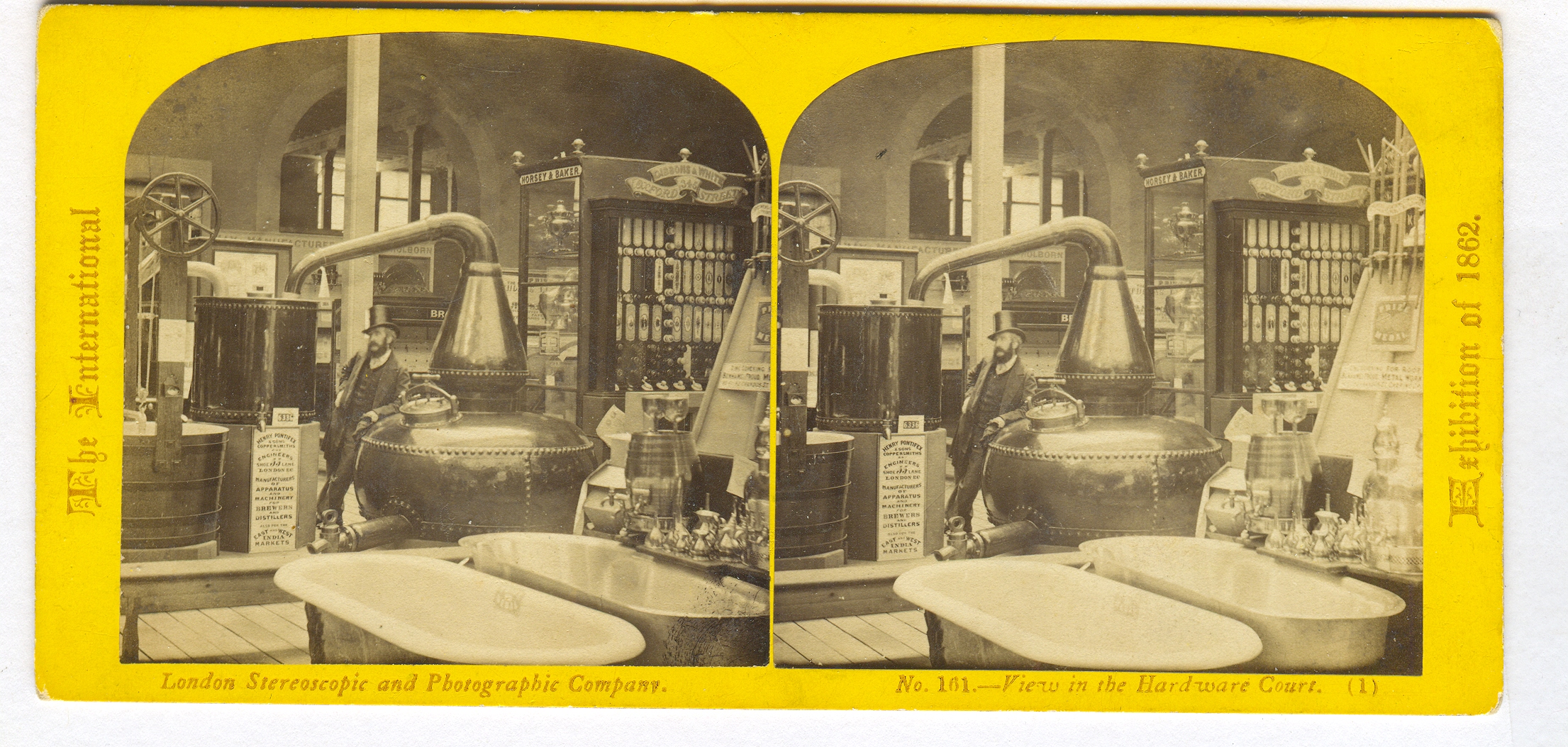

Fig

4. View in the Hardware Court. Enameled baths and a still.

Fig.

5. The Tasmanian Court. An eclectic mix of objects.

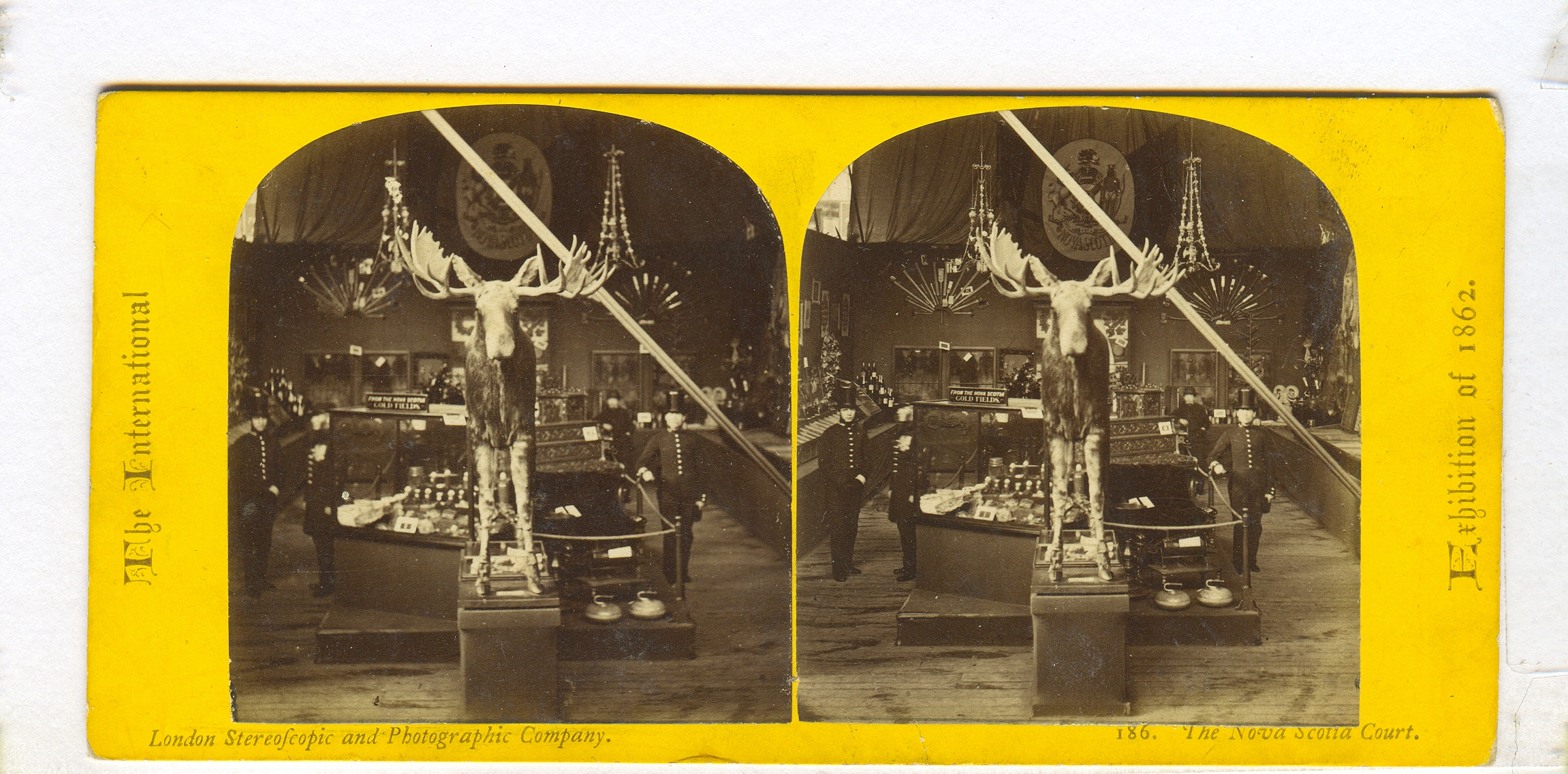

Fig.

6. The Nova Scotia Court (with Exhibition constables).

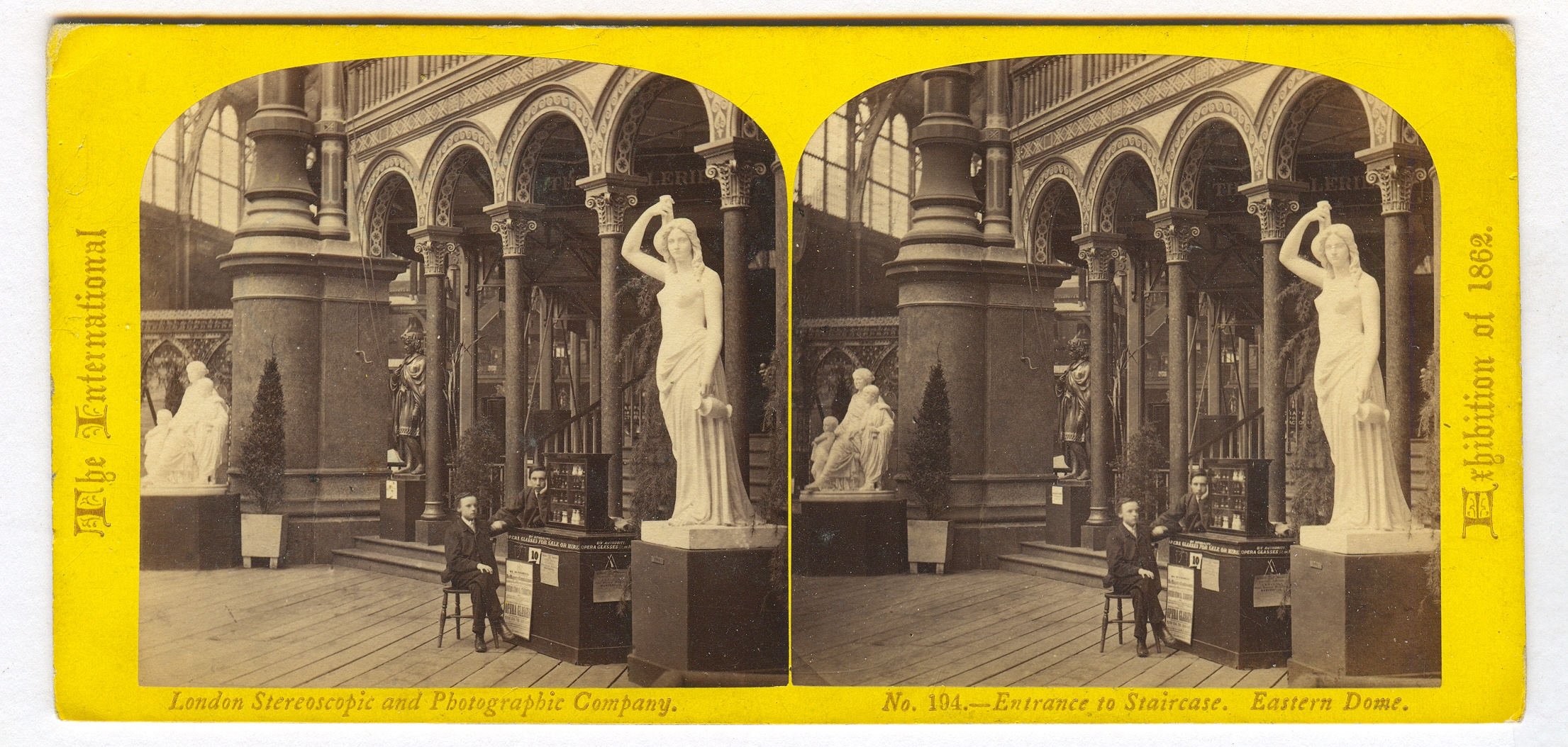

Fig.

7. Entrance to staircase, Eastern Dome. The stall is selling opera glasses

for closer viewing.

Fig.

8. French Machinery, Western Annex (1). One of four fascinating views of

the French machinery exhibits.

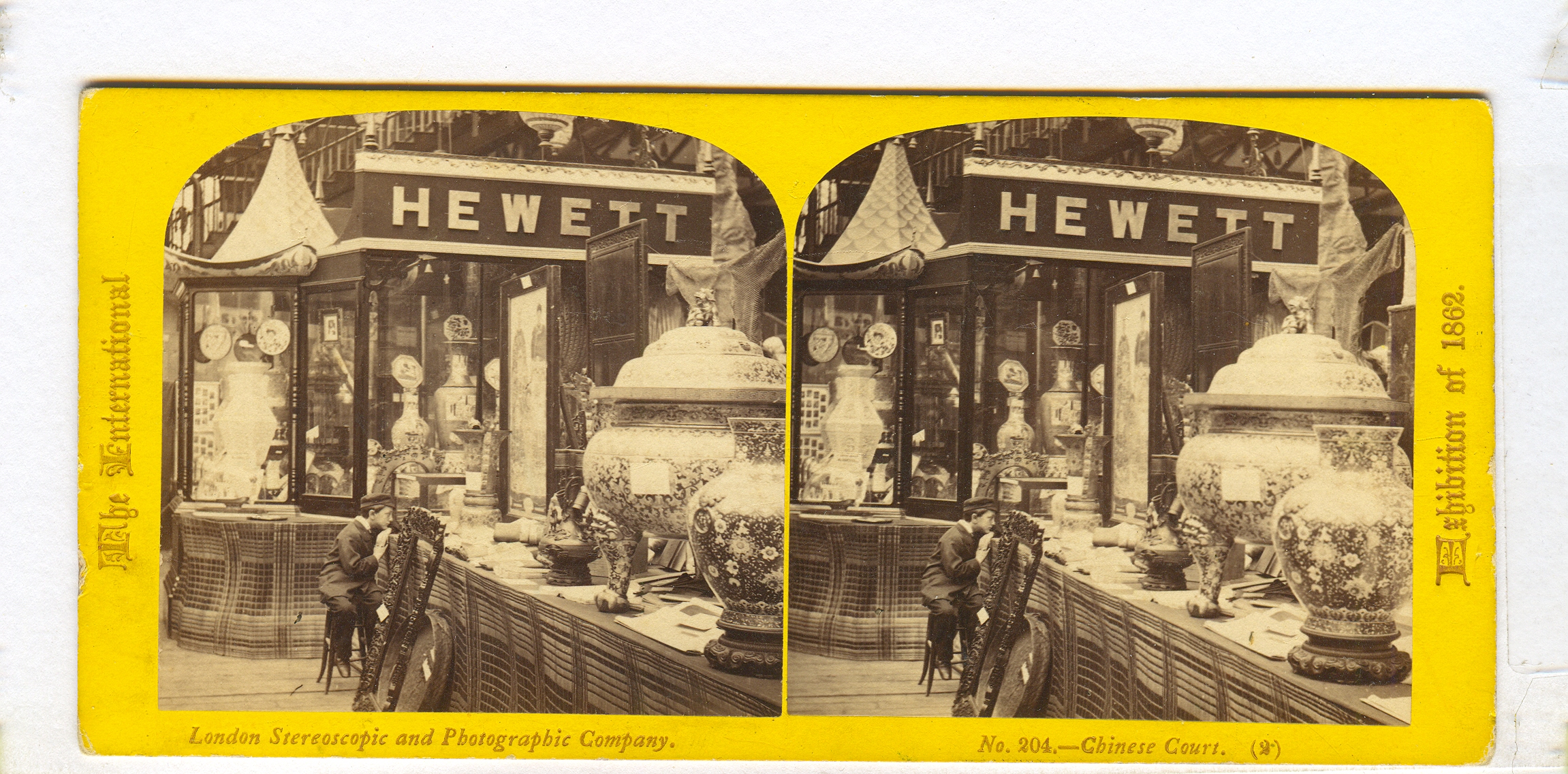

Fig.

9. Chinese Court (2). One of three views of the Chinese exhibits. Eagerly

sought-after, these are probably the highest value views at present.

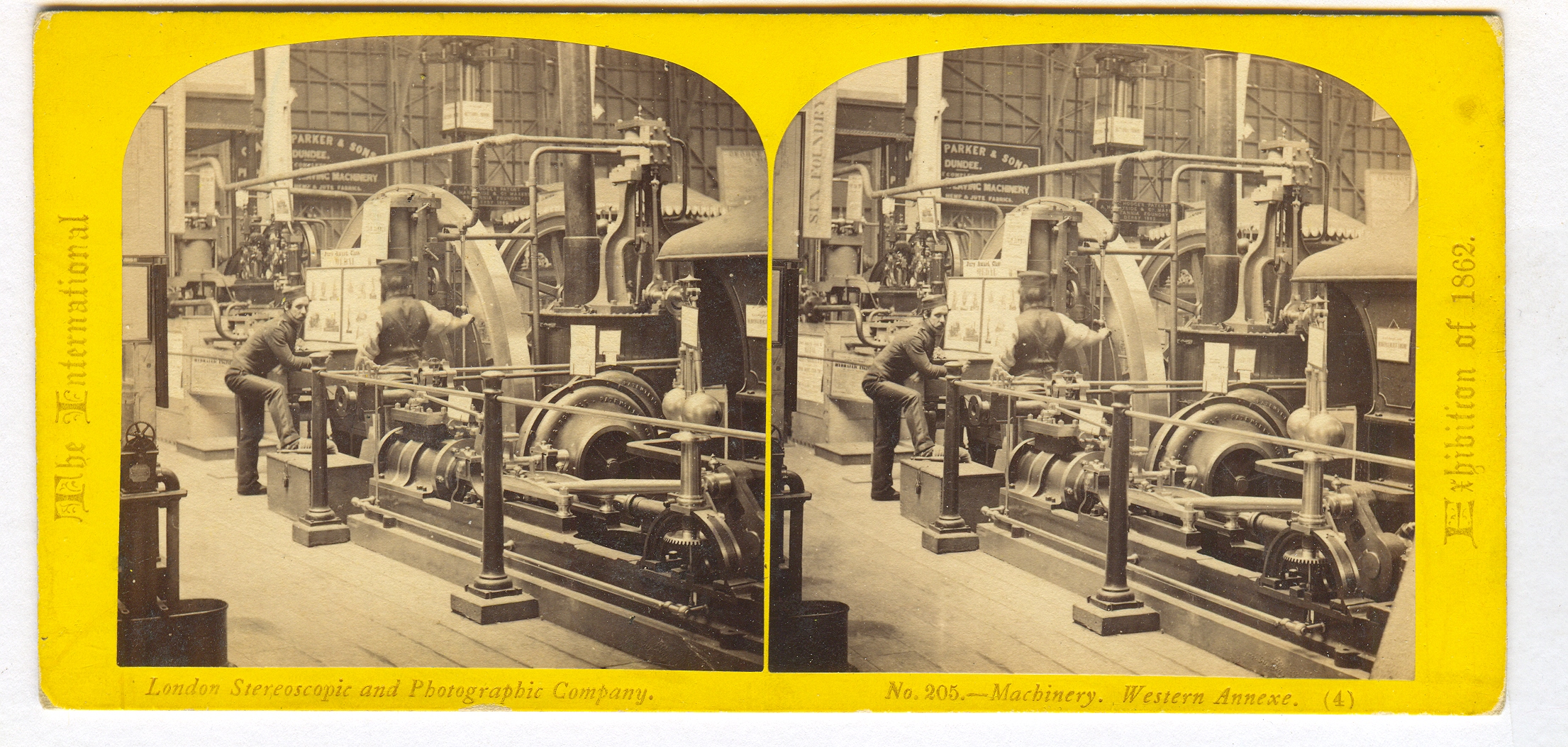

Fig.

10. Machinery, Western Annexe (4). Another fascinating view.

Fig.

11. Process Court. Velvet weaving. This is an exceptionally rare view.

Fig.

12. View in the Zollverien Court. The Zollverein was the customs union

between various German States before Bismarck unified them.

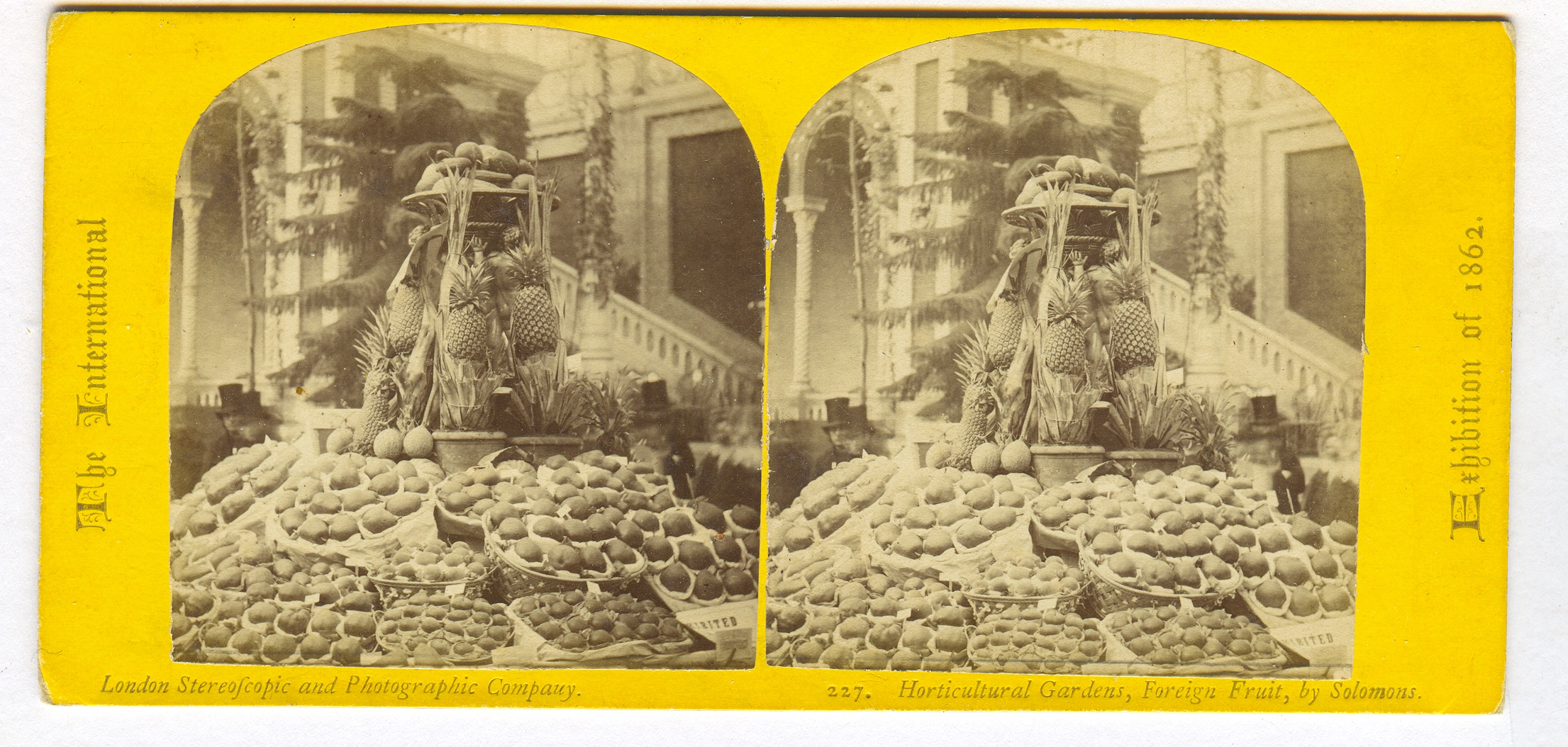

Fig.

13. Horticultural Gardens. Foreign fruit, by Solomons.

Fig.

14. A rare external view from the Horticultural Gardens.

Fig.

15. The Eastern Annexe, No 1. Strangely not much photographed and more

interesting than the Western Annexe.

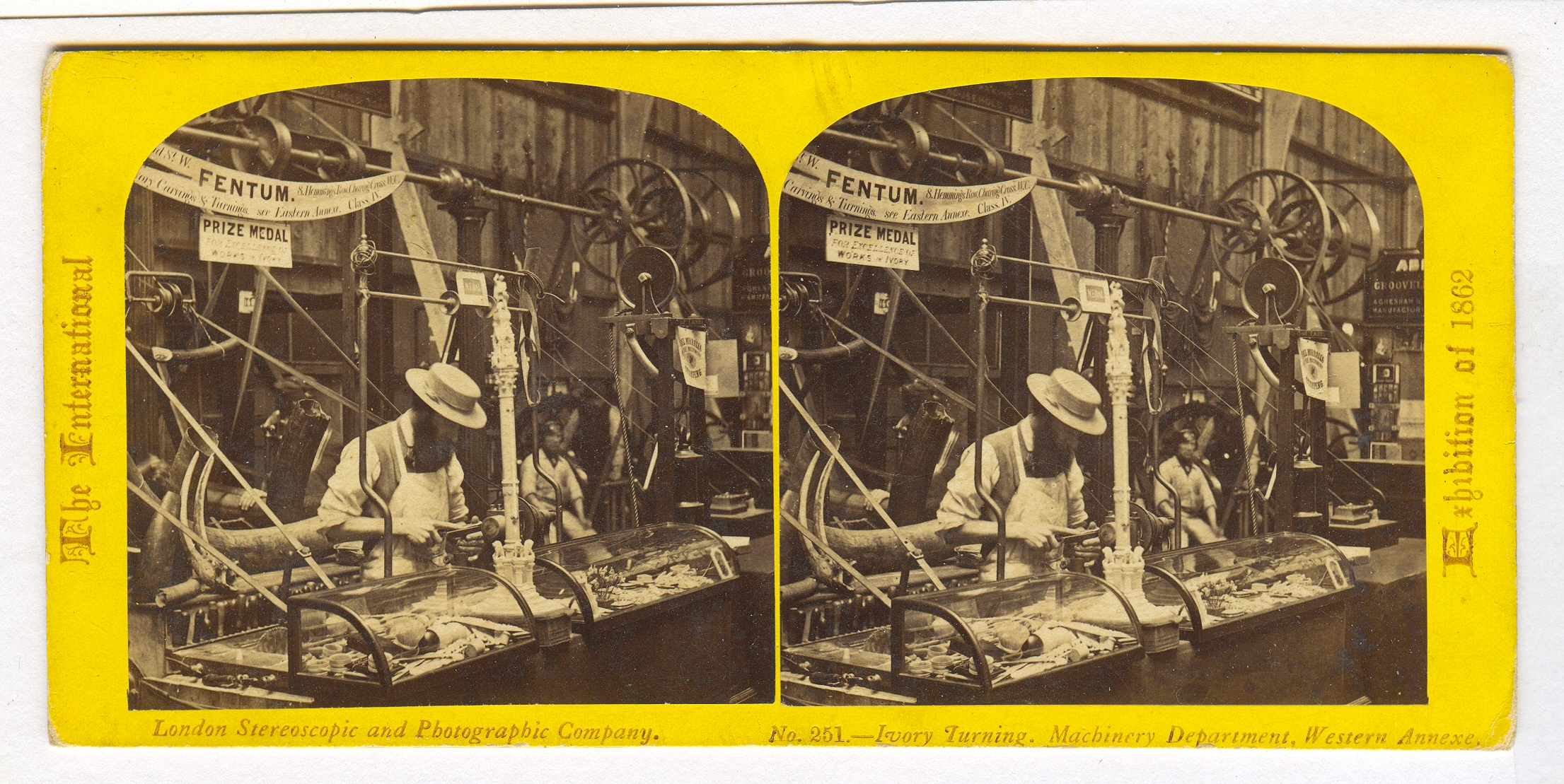

Fig.

16. Ivory turning, Machinery Department, Western Annexe..

Fig.

17. Process Court, sewing machines.

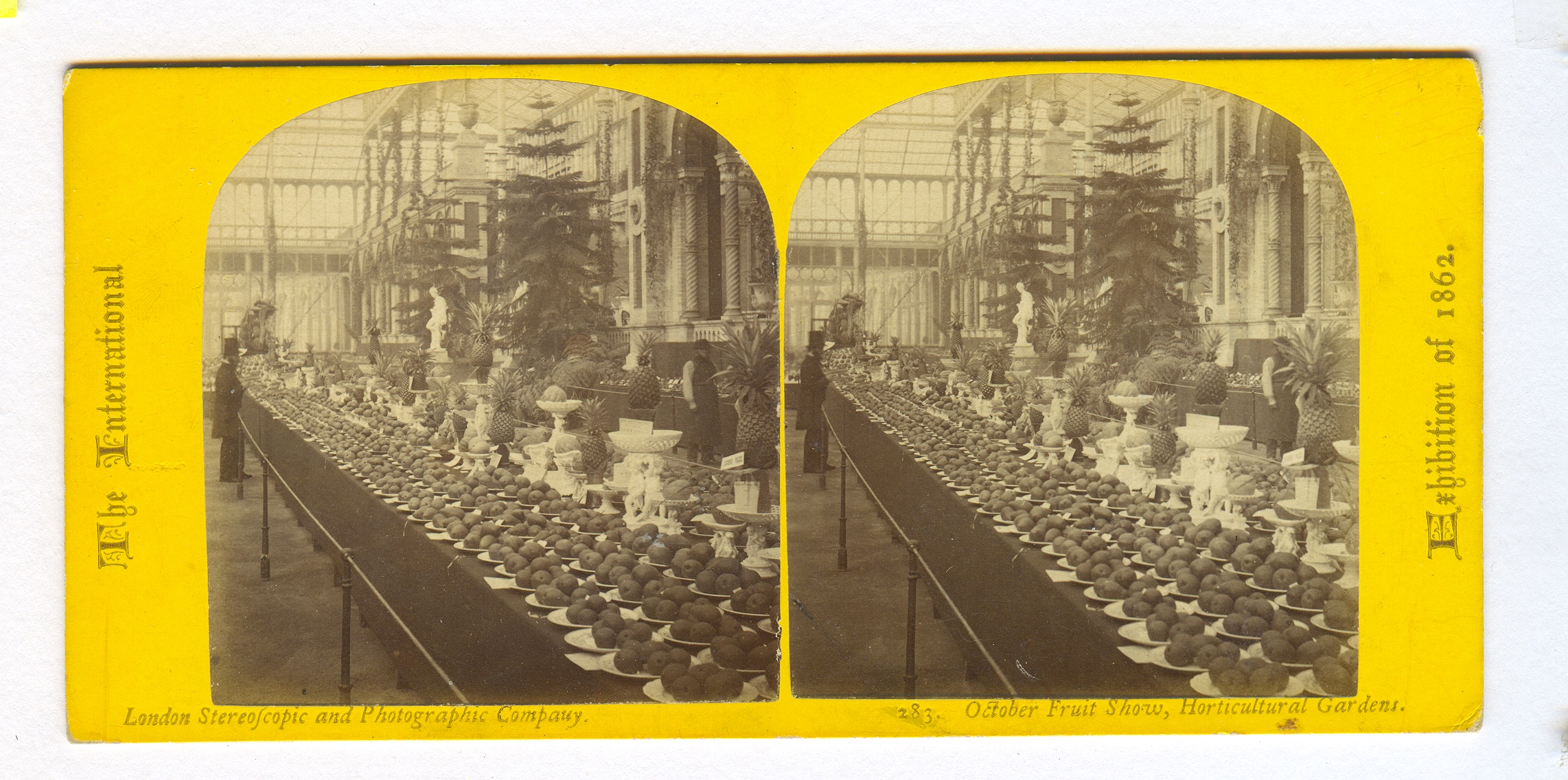

Fig.

18. October fruit show, Horticultural Gardens.

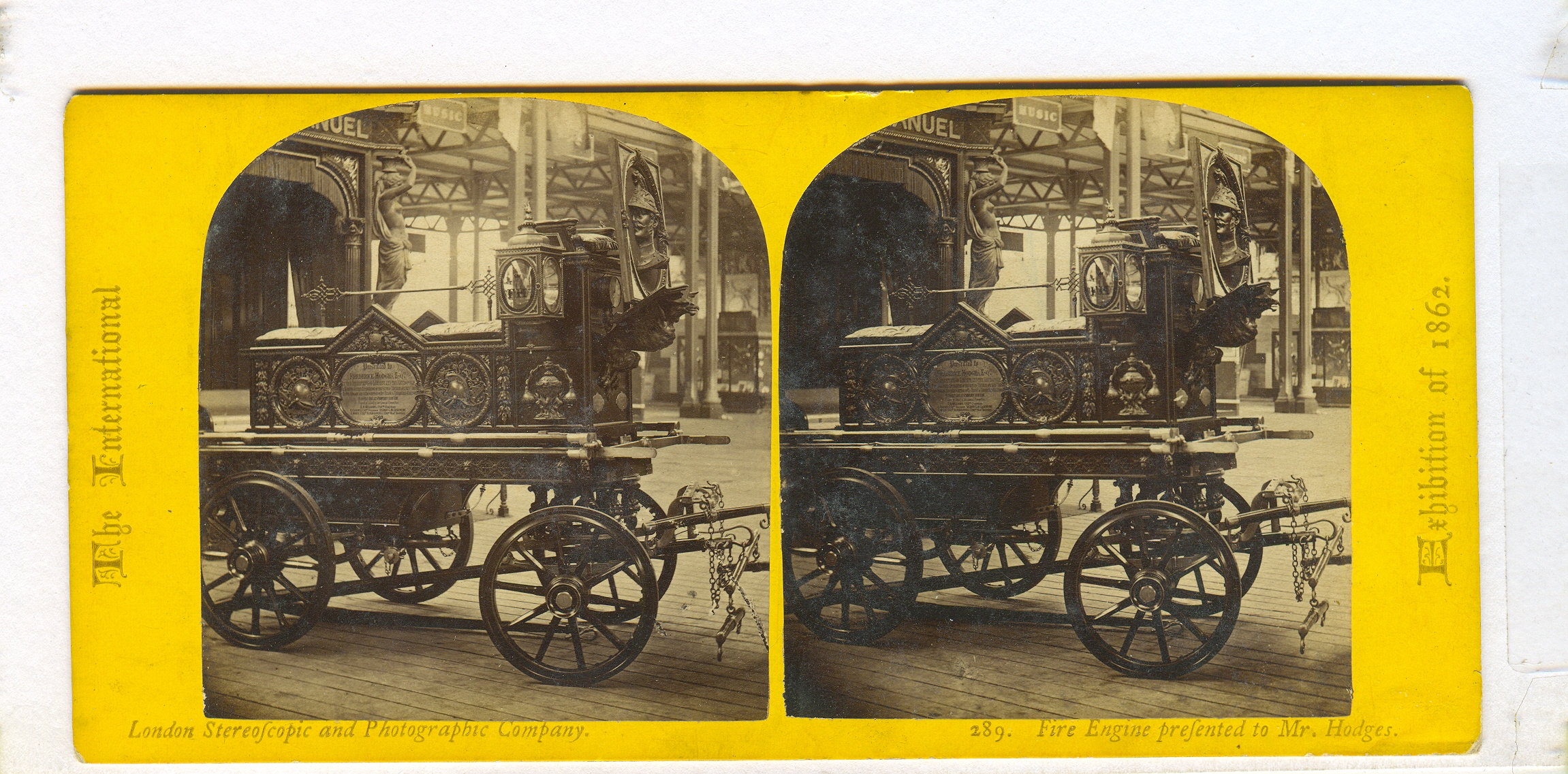

Fig.

19. Fire engine presented to Mr Hodges. This machine has an interesting

history. It was presented by the people of Lambeth to George Frederick

Hodges of the Lambeth Distillery for his services to firefighting and was

one of the three most powerful engines in London at the time. It is preserved

to this day and can be seen at the Museum of London.

Fig.

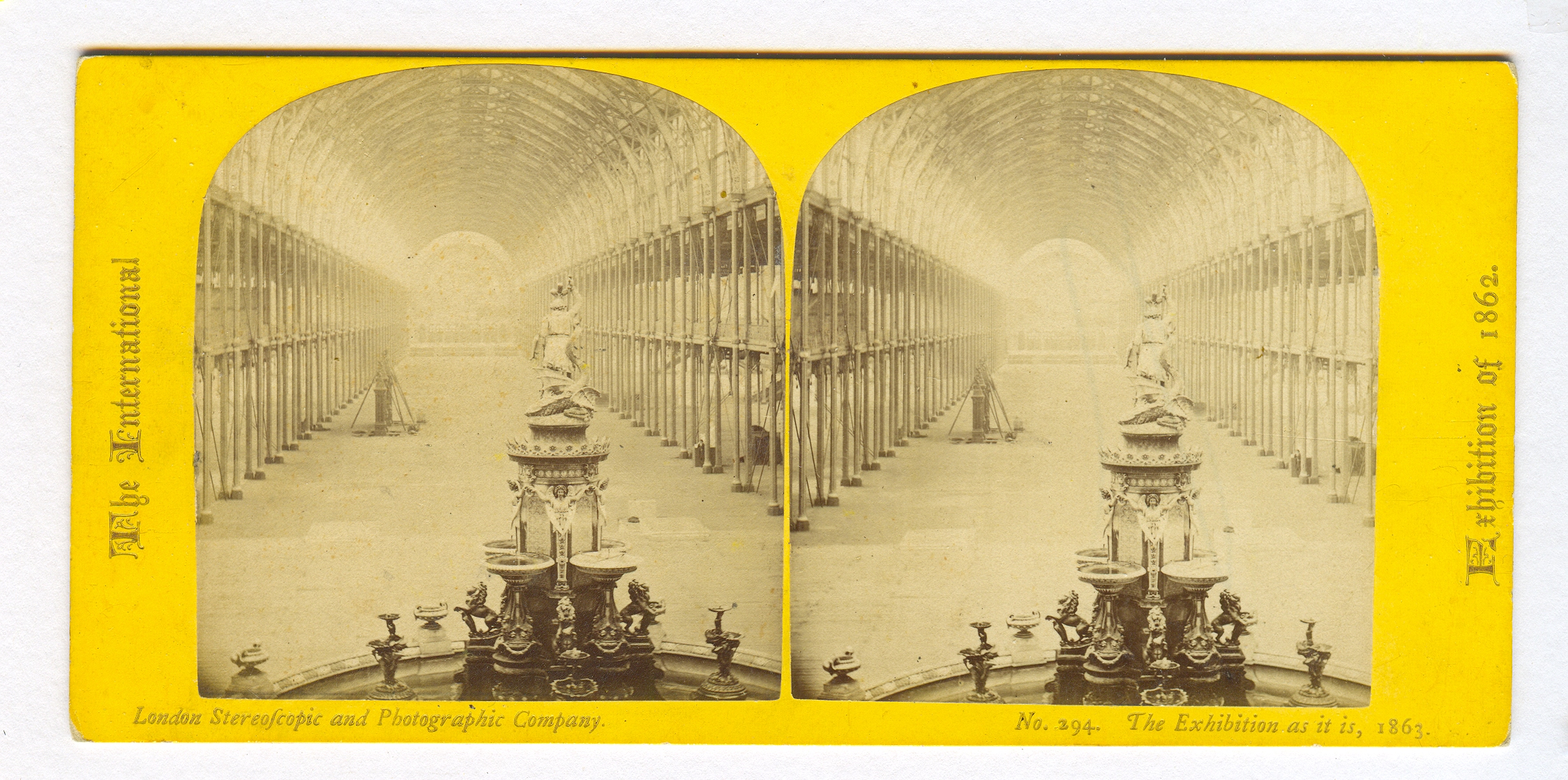

20. The Exhibition as it is – 1863. Totally deserted except for the Minton's

Fountain which waits to be dismantled. How they expected to sell this view

I have no idea. Obviously they didn't, as this is the only copy I have

seen.

Image from the Museum of London

Image from the Museum of London